W2: Ideology and the Orwellian

The notion of ideology is one of the most complex—and perhaps for that reason one of the most widely misunderstood—theoretical concepts. The usual entry points, such as Terry Eagleton’s book Ideology, can quickly overwhelm the newcomer with distinctions and definitions; Eagleton alone comes up with six different definitions of ideology by the end of the book’s opening chapter. More accessible introductions such as the Slovenian theorist Slavoj Žižek’s in Sophie Fiennes’s documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012) are recommended, but can also be quite confusing.

I recommend the opening sequence, in which Žižek uses the example of the 1980s film They Live as an introduction to thinking about ideology.

The standard introductory text on ideology is the French Marxist theorist Louis Althusser’s chapter which I’ve assigned. It’s also not an easy read (this is theory, after all), but the section at the end about the process of what Althusser calls interpellation (aka “hailing”) as one of the key operations of ideology is a bit easier to understand. It’s related to the notion of subjectivity and Althusser’s key idea that ideology continually addresses us, and constructs our identities, as subjects, in the political sense of the term “subject” (people who are the subjects of a monarch, etc.). In other words, ideology isn’t just a set of ideas and values that we take for granted as “normal” or “natural” (which is part of it), but more fundamentally, it shapes our very sense of who we are, our sense of our own identity and its relation to the wider world; our subjectivity, in other words. One of the ways it does this is by what Althusser calls “interpellating” us–calling out to and addressing us as particular kinds of subjects. For example, within the ideology of capitalism (only one kind, but the dominant one within which we are all immersed and that frames our sense of identity unless we are, say, anarchists or communists), the institution of advertising interpellates us as subjects: that is, it continually and directly addresses us, calling upon us to participate in capitalism as responsible citizen-consumers by consuming a multitude of commodities (including of course media commodities) and services that keep markets for these commodities and/or commodified services ticking over and growing. On a more general level, advertising is based on and reproduces the basic assumption that capitalist exchange is a “normal” and “natural” practice.

It isn’t just advertising that interpellates us in this way, of course. Governments and their related institutions continually interpellate us as national citizens, in the direct address to us of political leaders, government representatives, the police, or news anchors. It’s no coincidence that Althusser’s example of interpellation involves a policemen calling out to us “Hey you!”. In different ways, all of the messages politicians and government institutions address to us do the same thing—here in the UK, for example, one of the most irritating messages that interpellates us constantly on trains, the subway, or at airports is “If you see something, say something” and its related slogan, “See it, Say It, Sorted”. This addresses “us” collectively as responsible national citizens united in our opposition to and struggle against unspecified “terrorist” others seeking to attack our society. Ideological interpellation is at its height during wartime (especially for recruitment: “England needs you!”), and persists in commodified form in the merchandise of “Keep Calm and <your message here>”.

If our subjectivity roughly corresponds to the mode of address of interpellation, we are likely to receive these ideological messages without a second thought; it’s only if you have a different kind of identity or subjectivity that you notice, for example if you are watching French news (assuming that you can understand French) as a non-French person.

Ideology and its practice of interpellation arent’ just limited to the political or economic (capitalism) domains though. If you are a woman, especially a feminist, living in a patriarchal society, for example, you will no doubt notice (and feel alienated by) its continual interpellation of male heterosexual subjects and ignoring of women (“Hi guys!”). If you identify as non-binary, you will be in constant struggle with the oppressive heteronormativity and binarism of the dominant culture. If you are a vegan, you will notice the dominant ideology of meat-eating and how it continually assumes that it is the norm to which vegetarianism or veganism is the exception (although this of course has changed significantly in recent decades). But to white cisgender meat-eating heterosexuals (!!!), everything they do is “normal” because their identity is framed by their ideology that they remain unaware of it until it is pointed out to them. As Žižek points out, this is an uncomfortable process, since ideology is what to “us” (i.e. the people within a particular ideology) feels normal and natural. Having your ideology challenged by someone, or leaving it, is a painful process that forces you to leave your ideological “comfort zone”.

What is your position on hunting animals? Did you grow up in a family that has routinely hunted animals for generations? Try discussing that with an animal-rights activist. This is a conflict not just between two different ideologies—in this case, an “anthropocentric” ideology that considers animals as inferior and not entitled to the kind of rights that humans have, and a “non-anthropocentric” ideology that contests this—but between two fundamentally different forms of identity and subjectivity. As this example shows, ideology is inseparable from language, or more specifically what Michel Foucault calls discourse (which you can think of as ideological language), and arguments about ideology are often arguments about language: “anthropocentric”, for example, is a relatively recent term that originates in the discourse of animals rights, precisely as a critique of anthropocentric ideology. On the other side of the political spectrum, the term “woke” is a term used by dominant social groups to frame efforts to challlenge their dominant position in political hierarchies and their control over the forms of representation that circulate within it.

Capitalist Realism

Mark Fisher’s concept of capitalist realism, outlined in the introduction to his 2009 book of the same name, marks an attempt to identify an ideology produced within and about capitalism itself since the collapse of Eastern European communist dictatorships at the end of the 1980s. While the concept of capitalism itself of course originates in the much older discourse of Marxism, it’s the notion of realism that is the ideological core of the concept. “Realism”, in this context, is the apparently ideology-free assumption that in declaring that the fall of Communism demonstrates that—for all its faults—there is simply no alternative to capitalism, no other political-economic-social way of life outside it, one is simply being realistic; as if this was simply the reasonable conclusion that any rational person would reach. In fact, it’s precisely where such “rational” or “objective” explanations are invoked that we are most likely to be in the domain of ideology, since to invoke “reason” or “objectivity” is itself a deeply ideological move. In this case, the objective of the ideology is to ensure the continuation of the existing (capitalist) status quo by pre-emtively closing off any possibility of imagining any other ways of living beyond it. To do so, it can be argued, is in itself an inherently ideological move (since ideology always wants to assume that it is the “right way”), but also a political move.

The short section from Mark Fisher’s lecture about what he calls “postcapitalist desire” (or the lack thereof…) I think provides a mini-case study in the operations of capitalist realism and how it operates in contemporary media culture and is reproduced by it. The 1984 superbowl commercial is widely regarded as a classic event in the history of advertising, but to my knowledge has not been subjected to the kind of ideological analysis that Fisher gets into in those few pages. Anyway, here are the two 1984 commercials that he references in the lecture. Take a look at them and then (re)read the except from the lecture.

Returning to what I was saying earlier about advertising and ideology, we can see that both the Apple and the Levi’s commercials are interpellating “us” (we Americans in this case) as (consumer) subjects who they want to agree with the (capitalist-realist) worldview they present, in other words as people from the cool, colorful capitalist world rather than the bleak monochrome one of communist totalitarianism. Deep down, both commercials suggest, everybody wants Apple computers or Levis, even if totalitarian regimes deny them access to it.

In ideological terms, what’s interesting about the Apple commercial in particular is how advertising itself is invoking “ideology” as it is commonly framed by capitalist realism, as something that equates George Orwell’s classic dystopian novel 1984 with Eastern-European totalitarianism (declining but still very much alive when the commercial was made, of course). What’s interesting in this case, though, is how Apple is sort of mapping the political distinction between totalitarian conformity and revolutionary freedom onto its own relationship to its economic competitor, Microsoft: most explicitly in the resemblance between the bespectacled Great Leader on the screen and Bill Gates! So Apple is in a way co-opting the visual language of political revolution as a marketing strategy by positioning its competitor as a “boring”, autocratic regime being overthrown by a “revolutionary” insurgent (ie. Apple). This has become a common strategy in advertising and promotional culture, where “Revolution” is often coopted in branding and marketing (consider MTV’s 1980s slogan, “Revolution™”).

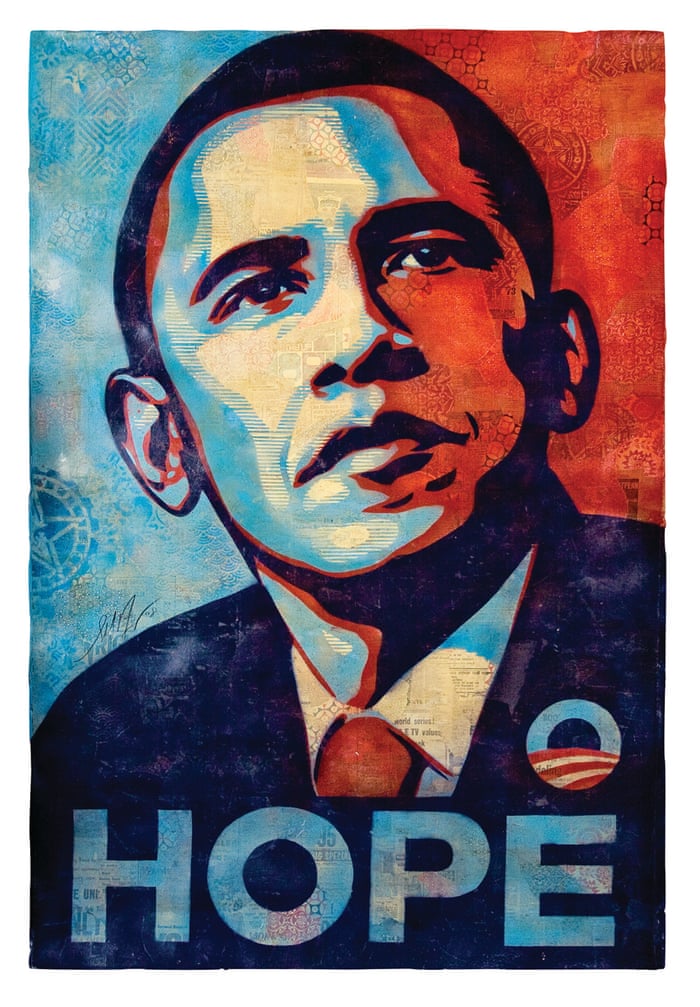

Many similar examples could be found today. A particularly interesting example is the graphic artist Shepard Fairey’s iconic poster of Barack Obama that became ubiquitous in Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. Prior to the Obama poster, Fairey was better known as the creator of the André the Giant “Obey” poster (see image above). The “Obey” poster can in fact be seen as an early example of advertising’s coopting (in ideological terms this is called “recuperation”) and commodification of the visual iconography of totalitarianism itself, along with its counterpart, revolution, in the endless variations on the iconography of the Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Tse-Tung or the Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara. Shepard Fairey has converted his propaganda-inspired images into a highly successful brand.

One can, of course, find innumerable examples of such “post-Communist” capitalist realism in everyday media culture. Even the dreary architectural realities of 1970s Communist architecture and everyday life have today been reified (turned into commodities) objects of nostalgia in “post-Soviet” aesthetics.

Meanwhile, streaming platforms such as Netflix are awash in hugely popular drama series that are allegedly also examples of what Fisher calls capitalist realism. Paradoxically, capitalist dystopias are among the most popular forms of commercial entertainment. A case in point is arguably the hugely-successful Korean series Squid Game, a show that while ostensibly a satirical critique of the social and economic injustices of capitalism (notably its system of debt), arguably serves to reinforce the ideological idea of the inescapability of capitalism itself: in the world of Squid Game as in so many other similarly “anti-capitalist” series and movies, there is simply No Alternative.