W4: Material Girls: Feminism After Feminism

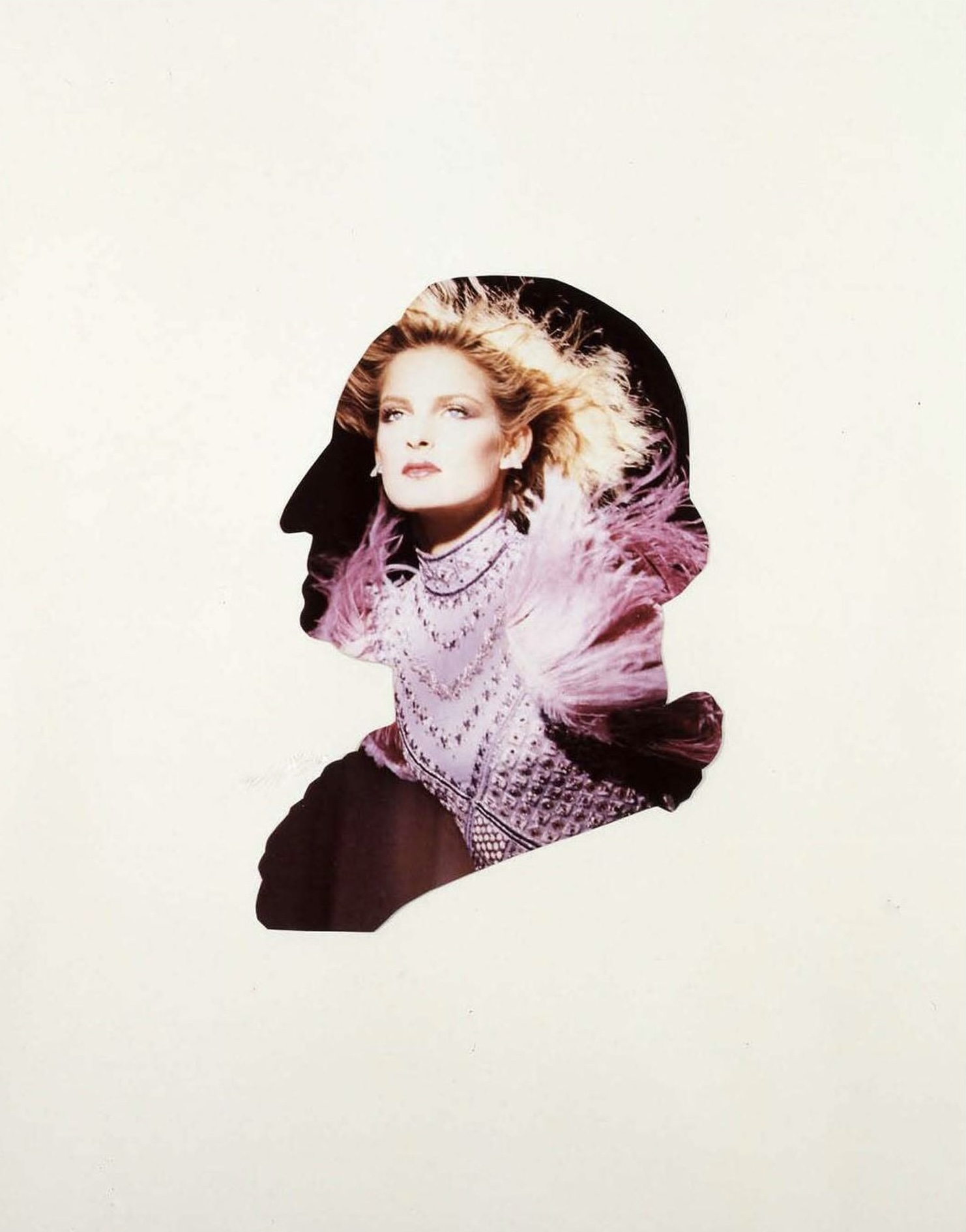

Sherrie Levine, President Collage: 6, 1979

Feminism After Feminism

Along with fields such as semiotics, Marxist political economy, psychoanalysis, and postmodern(ist) theory, since the 1970s feminist theory and its many offshoots has emerged as one of the most influential critical frameworks in film and media anaylsis. “Feminist theory” here encompasses a wide range of gender-based theoretical approaches, from the common historical framework (first-wave, second-wave, third-wave) to postfeminism, cyberfeminism, and its most recent iteration, xenofeminism. What these diverse approaches have in common is an analysis of the repressive political, social, and economic structures of modern patriarchy, their historical subjection of women both in everyday life and media representations, and the project of emancipating women from them which continues into the present.

I don’t have a lot of time to get into the details of postfeminism here, which has become one of the most popular but also one of the most widely critiqued currents within feminism since the 1980s. For that, I will simply refer you to the excellent introduction to Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra’s influential anthology Interrogating Postfeminism from the early 2000s. The accompanying reading assignment to it, my own article on fashion makeover shows in lifestyle television, provides a case study in what I saw as one of the most striking popular implementations of postfeminist ideology at the time, the British (and subsequently American show What Not To Wear). Although dating from almost two decades ago now, my analysis of the show may perhaps bring to mind some more contemporary examples, as well as encouraging us to reflect on and discuss what has become of “postfeminism” several decades on. I’m curious to hear your thoughts on that, and have some thoughts of my own about it which I lay out below.

The Word Girl

To do what I should do

To long for you to hear

I open up my heart

And watch her name appear

A word for you to use

A girl without a cause

A name for what you lose

When it was never yours (oh-oh do-do-do)

. . .

A name the girl outgrew

The girl was never real

She stands for your abuse

The girl is no ideal

It’s a word for what you do

In a world of broken rules

She found a place for you

Along her chain of fools (oh-oh do-do-do)

—David Gamson, Green Gartside [Scritti Politti], “The Word Girl” (1985)

See the course YouTube playlist for other examples of “girl” pop songs.

Everyone is female, and everyone hates it.

—Andrea Long Chu, Females (2018)

Girl’s gotta eat.

—Alex Quicho, “Everyone is a Girl Online”

From the standpoint of feminist theory, one possible starting point for critically engaging with contemporary constructions of female identity is the current ubiquity of the word girl, and debates about it, in the polyphonic discourses swirling across social media. Perhaps the key observation here appears to be the displacement of the feminist term woman itself by the ubiquitous girl, as well as the equally ubiquitous use of female—as a noun rather than an adjective—as theorized in Andrea Long Chu’s influential book Females (2018).

The term girl has in recent decades become an object of increasing theoretical interest, notably in a much-debated work by the French Tiqqun collective, Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young Girl (1999, Eng. trans. 2012).

The collective argue that in postmodernist society and its accompanying digital culture, the identity of the “girl” has become inseparable from commodity culture and mass consumption. Andrea Long Chu goes even further, attempting in her book to disarticulate the term female from its connection either to anatomical biology or constructions of gender identity, framing it instead simply as a structural position of subservience and subjection. From this point, even biological men can be framed as “female”. In her controversial WIRED article, feminist theorist and cosplayer Alex Quicho draws on both Tiqqun’s and Andrea Long Chu’s texts to elaborate the audacious and apparently counterintuitive claim that “Everyone is a Girl Online”. Chu’s project of disarticulating femininity both from anatomy and gender seems vindicated in the ubiquitous social media trend of the babygirl, a biologically male but adorably tearful “sad girl” embodied by Kendall Roy from HBO’s series Succession or Pedro Pascal in… well, pretty much anything.

Alex Quicho, “Everyone is a Girl Online” (WIRED, 11 September 2023)

Emma Copley Eisenberg, “Notes on Frump: A Style for the Rest of Us” (heyalma, 10 August 2017)

Contrary to postfeminist enthusiasts of online girldom, we have Emma Copley Eisenberg’s critique of what she calls the Sexy Adult Woman [SAW] ideal through her defence of what she calls Frump, a modality of female identity deliberately oppositional to the patriarchal imperative of appealing to the cisgender male gaze. Inspired by Susan Sontag’s famous essay “Notes on Camp”, Eisenberg’s article “Notes on Frump: A Style for the Rest of Us” makes a compelling case for a form of contemporary womanhood in opposition both to the Young Girl and her grown-up counterpart, the SAW.

Mother

A second starting-point for thinking about female identity in the contemporary world is to do with motherhood and reproductive rights. The contemporary theorists that I would direct you to in this area would be Helen Hester, Joanna Zylinska, Bogna Konior, and the xenofeminists members of the Laboria Cubotniks collective, authors of the Xenofeminist Manifesto. Representing perhaps the most radical current within contemporary feminist thought, the xenofeminist group developed out of the cyberfeminism of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. In keeping with Haraway’s figure of the cyborg as a kind of ideal for women’s engagement with technology, the xenofeminist group (as far as I understand it) embrace technology in the broadest sense for its potential for liberating women from their traditional role of domestic reproduction and caregiving.

With regard to media criticism and the critical frameworks mentioned above, it is interesting to look at representations of the mother in contemporary film and digital media culture, from the sardonic stereotypes of “soccer moms” and “mom jeans” to depictions of maternal agency in cinema, such as Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s 2009 thriller Mother. Perhaps you can think of some other examples that would be relevant to this discussion?

Social Media

To conclude, here is a list of what we might think of as a collection of (often contradictory) modalities of female identity in contemporary social media culture, laid out as a word cloud. Some of these terms are well-known stereotypes, others were more recently coined by some of the feminist writers discussed above. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on any of these terms, as well as suggestions you may have of others that I may have overlooked!

angel complex • bimbos • influencers • Karens • Barbie • beautiful princess disorder (BPD) • SAWs (Sexy Adult Woman) • soccer moms • mom jeans • mukbang (Korean food bloggers) • Japanese VTubers • I’m literally just a girl • wanghong (Chinese influencers) • Xiaoyongshu girls •